The Retroavangarda Gallery presents the graphic works and paintings of the outstanding artist Hanna Zawa-Cywińska at the 22nd Warsaw Art Fair – stand G14. Below, we present a brief biography of the artist and texts written by renowned Polish art historians.

Hanna Zawa-Cywińska – Life and Work

Essay by Andrzej Matynia

Bożena Kowalska on the Art of Hanna Zawa-Cywińska

Marek Bartelik on Hanna Zawa-Cywińska

Life and Work

Hanna Zawa-Cywińska (born 1939 in Łomża) – a Polish contemporary artist. She studied biochemistry and journalism at the University of Warsaw, and after leaving Poland in 1967, she pursued studies in advertising and graphic design in New York at the Fashion Institute of Technology and the State University of New York at Purchase, where she earned her degree in 1981. In the United States, she began her artistic career, becoming involved with the circle of Op Art and geometric abstraction artists. She collaborated, among others, with Polish-born Op Art painters Richard Anuszkiewicz and Julian Stańczak. During her stay and work in New York, she co-founded the Polish American Artists Society.

Since the 1980s, she has collaborated with Bożena Kowalska and Gerard Blum-Kwiatkowski, taking part in numerous exhibitions and artistic symposiums. In 1987, she held her first solo exhibition in Warsaw, and since 1991 she has been actively participating in Poland’s art scene. From 1994 to 2004, she lived and worked in Switzerland, where she was a member of VISARTE, and from 2004 to 2018 she divided her time between Paris and Warsaw.

Zawa-Cywińska has presented over 50 solo exhibitions and participated in more than 150 group shows across Europe, the United States, Japan, and Brazil. Her works are included in the collections of numerous museums worldwide, including the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C., the National Museum in Warsaw, the Museum of Art in Łódź, the MIT Museum in Cambridge, and the Tucson Museum of Fine Arts. She has received several distinctions, including the Art Directors Club Award in New York. Her works are also part of the David Bermant Foundation collection, which focuses on art integrating light and sound.

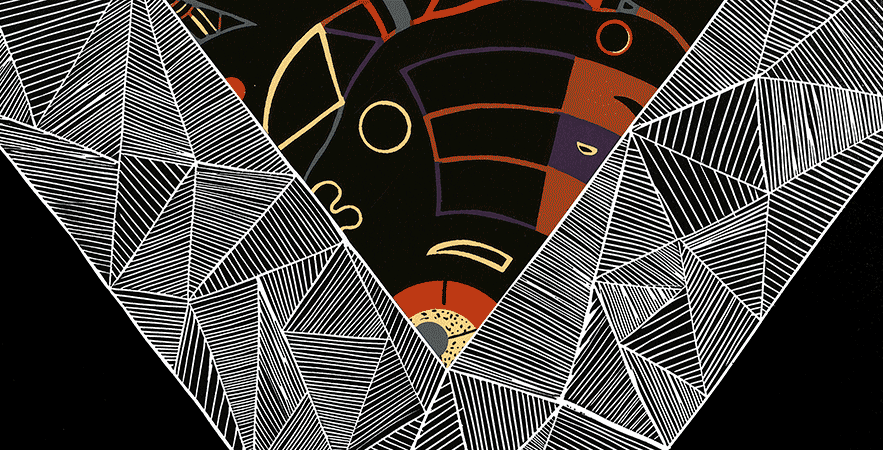

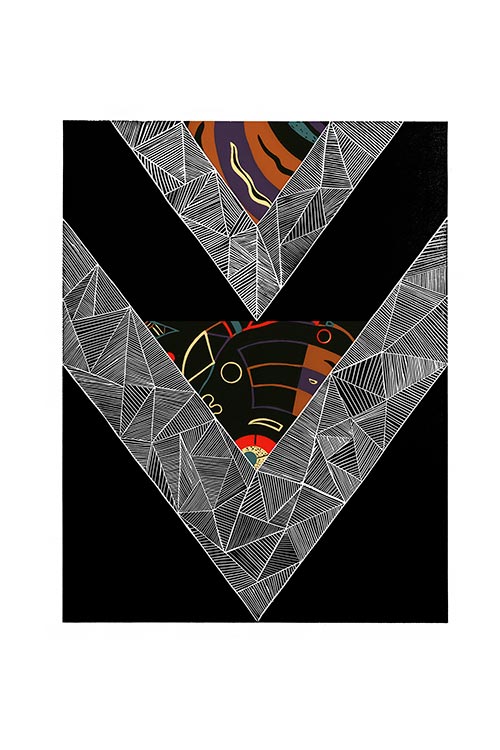

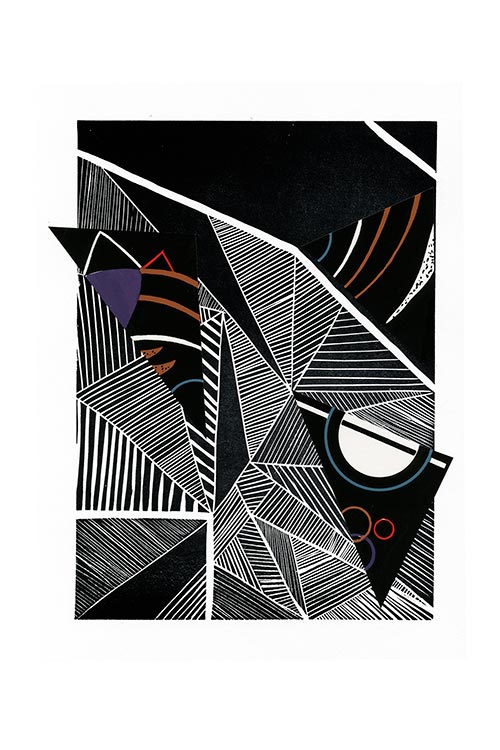

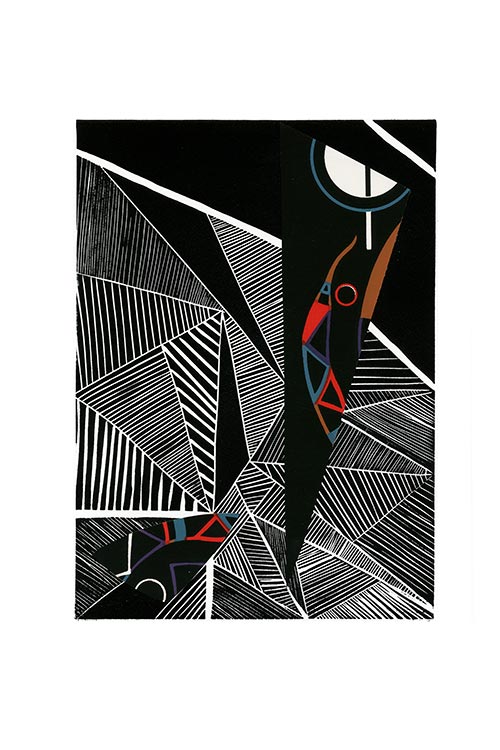

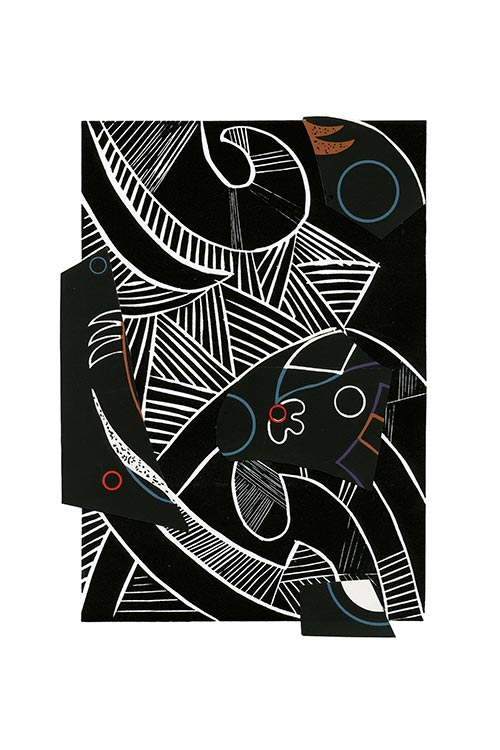

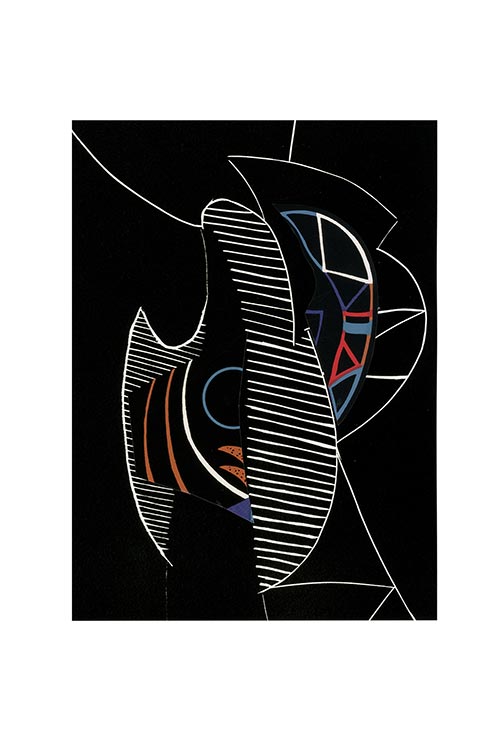

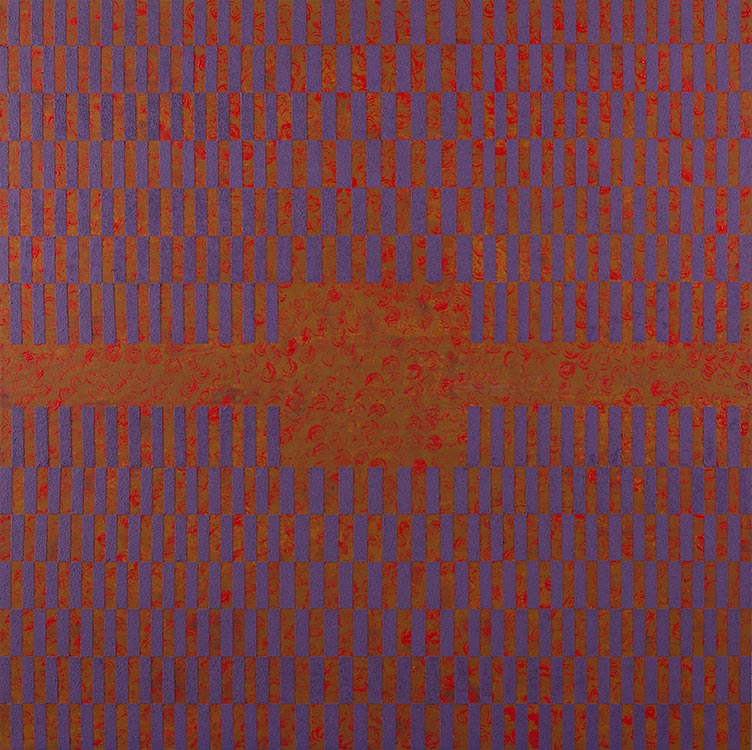

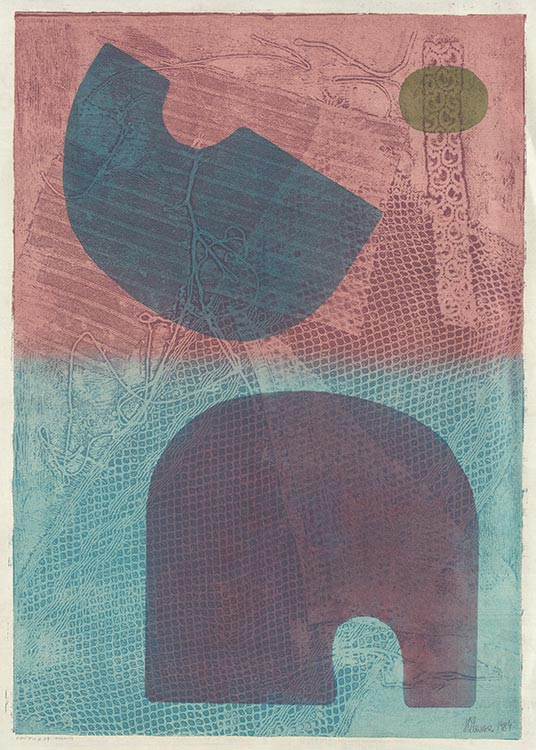

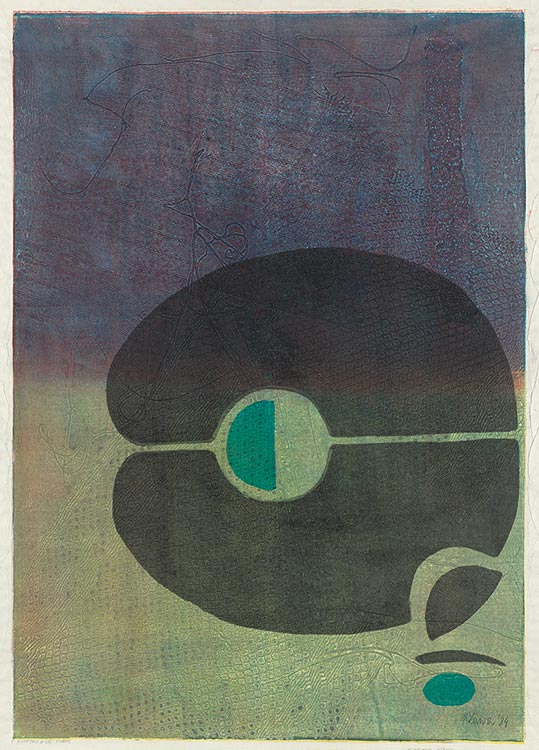

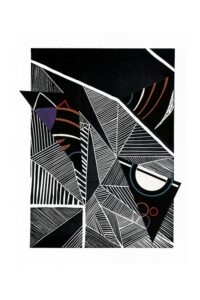

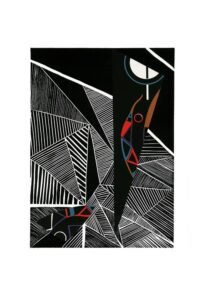

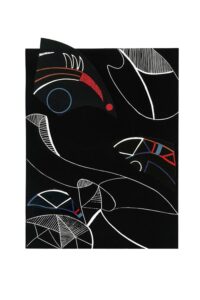

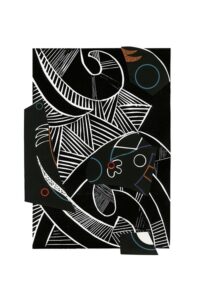

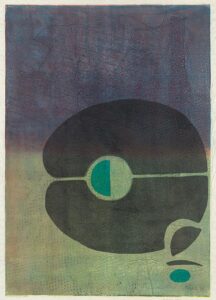

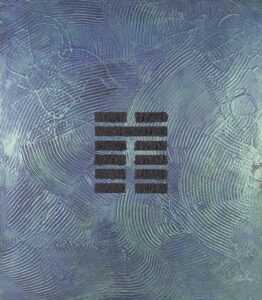

Among her most renowned series are I-Ching and Flirt with Kandinsky. In the latter, Zawa-Cywińska juxtaposed her own linocuts with fragments of Wassily Kandinsky’s lithographs, creating a visual dialogue with the master of abstraction. The compositions from this period combine rhythmic structures, intense color, and a profound spiritual reflection on the nature of art.

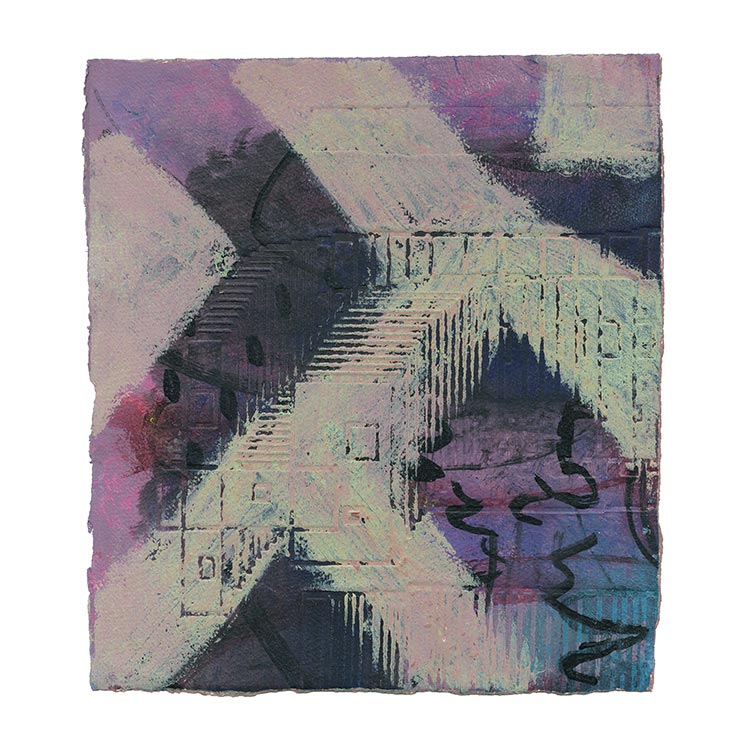

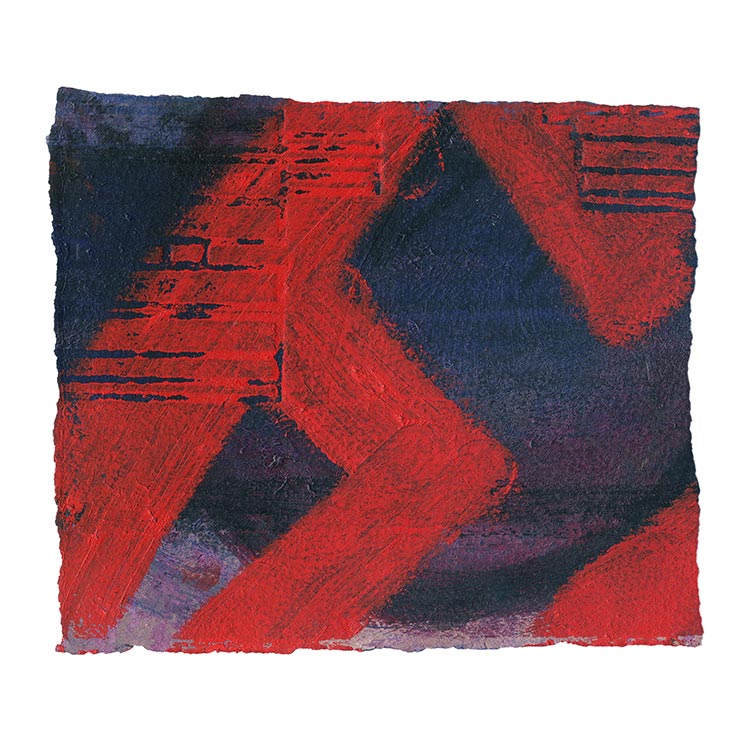

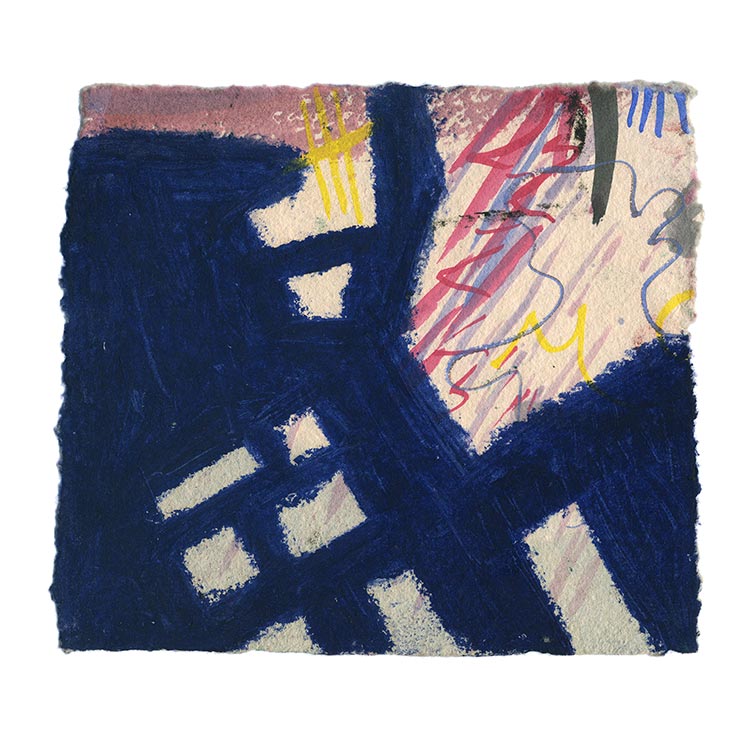

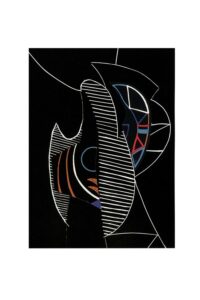

Selected Graphics from the “Flirt with Kandinsky” Series:

Essay by Andrzej Matynia on the occasion of the opening of Hanna Zawa’s exhibition “Works on Paper – Series: Flirt with Kandinsky” at the Andre Zarre Gallery in New York, March 1990.

In 1944, when Wassily Kandinsky passed away, Hanna Zawa-Cywińska was five years old. Kandinsky had opened a new chapter in American painting. Through the influence of Hans Hofmann, who emigrated from Germany to the United States in 1930, Kandinsky’s ideas spread among an entire generation of Abstract Expressionists. His notion of liberated color—freed from all constraints in accordance with “inner necessity”—found many followers in America.

However, when Hanna Zawa-Cywińska began her artistic journey, other tendencies dominated the art world. Artists programmatically rejected traditional painterly rules, proclaiming with nonchalance that a work of art is anything the artist creates, and anyone can be an artist. Over time, technology and its detritus entered the realm of art. Arman filled his objects with discarded radio tubes, while Jean Tinguely animated fairground-like sculptural elements using industrial motors and engines. Neon objects appeared as well.

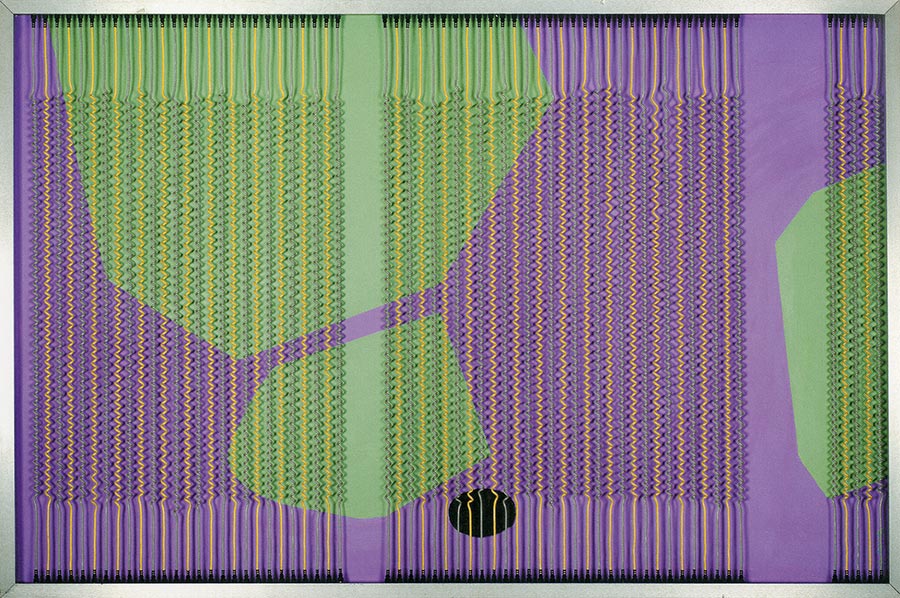

This trend did not bypass Zawa-Cywińska. Electronic cables were, after all, close at hand—her husband being an electronics engineer. From these colorful wires, she created large, two-plane compositions with rhythmic cable structures stretched a few centimeters in front of the pictorial background. The viewer, looking at them, experienced an illusion of movement, while electronic devices embedded within the works responded to the viewer’s presence with acoustic effects.

The artist also began using the computer in her graphic works. The computer impressed intricate structural reliefs onto the prints, which flowed across their surface alongside spontaneously applied patches of colored paper.

The spontaneous gesture of the hand combined with the automatic precision of the computer’s drawing produced a poetic tension symbolic of our modern civilization. At the same time, the irregularly torn and affixed fragments of colored paper—sometimes evoking biological forms, at other times approaching geometric shapes—revealed a yearning for the liberation of color.

In life, coincidences abound, but in art, almost never. Hanna Zawa-Cywińska came across a lithograph by Kandinsky. Certainly, chance played a role, yet Cywińska’s artistic path had been leading toward such an encounter. The lithographs were unsigned, and most were probably made from paintings—perhaps around the time of Kandinsky’s exhibition held in the winter of 1935–1936, or in 1945, when a major retrospective of his work took place in New York. These works undoubtedly came from the period after 1920, when geometric elements—straight lines, fragments of circles, squares, and triangles, later evolving into concentric arrangements dominated by spherical forms—entered his compositions.

Kandinsky was convinced of a constant relationship between color and form, believing that every form possesses an inner content. The chaos in Kandinsky’s paintings is ordered, for he sought not the liberation of automatism but the harmonization of forces to express cosmic and transcendental energies. He realized that concrete objects harmed his painting and thus entered the realm of abstraction. Toward the end of his life, his art changed somewhat, balancing delicately on the line dividing poetic intuition from scientific deduction.

Could Cywińska have found a better medium? She masterfully incorporated carefully chosen fragments of Kandinsky’s paintings into her linocuts, as postmodernists often do. She arranged the pictorial plane with finesse, allowing the color to resonate—we can almost hear its sound. We feel the fervor of a red area much as Kandinsky did, who saw in red an inward maturity, unconcerned with externality. For color, as modern science confirms—and as Kandinsky intuited—is not merely a matter of retinal stimulation but engages our entire biopsychic being.

Hanna Zawa-Cywińska’s prints are meticulous and sophisticated. She never subscribed to the proclamations of apocalyptic theorists announcing the end of art, nor did she believe in the decline of beauty, an idea temporarily dismissed by avant-garde circles. Yet, after the experiences of twentieth-century art, she is unlikely to confine painting within Poussin’s definition that “painting has no other purpose than the joy and delight of the eyes.” Such a view was unacceptable to Kandinsky—and it does not convince Cywińska either. Perhaps what unites them is a Slavic mysticism, one that never allows artists from our cultural sphere to reduce art to a mere form of play.

Andrzej Matynia, March 1990

Bożena Kowalska in her book “Creators – Attitudes” on the Art of Hanna Zawa-Cywińska

In all of Zawa-Cywińska’s works—her prints, paintings, and other forms of artistic exploration—there is a certain formal element that unites them. Although its shape constantly changes and thus is not immediately recognizable, it defines the very essence of her art and constitutes its individual character. This element does not stem from acquired models or external influences; it is deeply rooted in the artist’s personality structure.

This formal element—or, to put it more precisely, this method of formal composition—is the principle of using two superimposed layers that differ in nature. One might ask to what extent this is a conscious act and to what extent it is guided by intuition. Regardless of the mechanism, however, the approach remains consistent and deliberate.

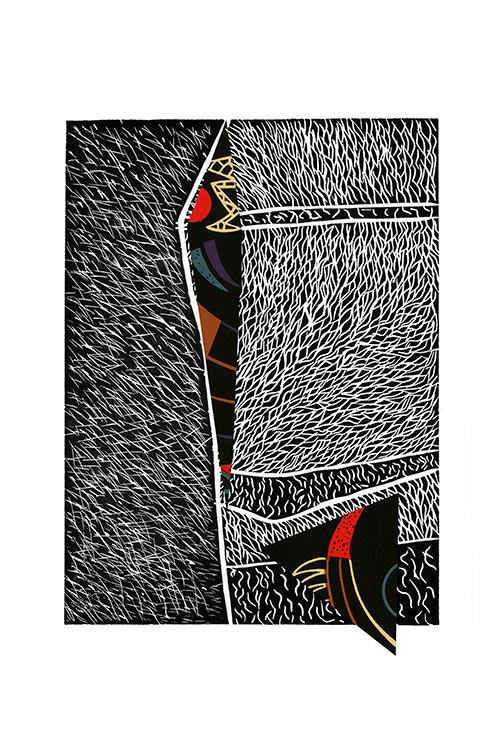

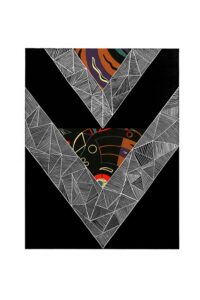

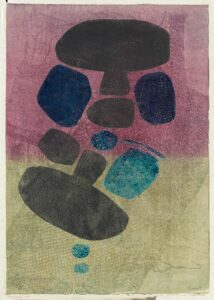

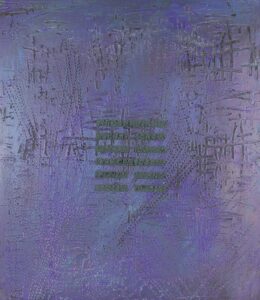

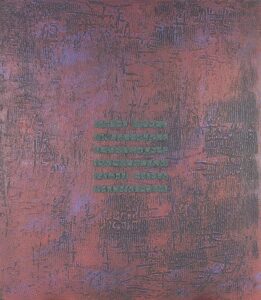

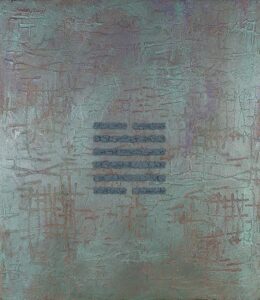

If one examines the successive phases or cycles within the artist’s oeuvre from this perspective, it becomes evident that this principle of duality has one more constant feature: in all of her works, regardless of technique, the upper layer acts as a kind of screen or veil, which—through its openings, cutouts, or sometimes a transparent mesh or grid—reveals the world beyond it.

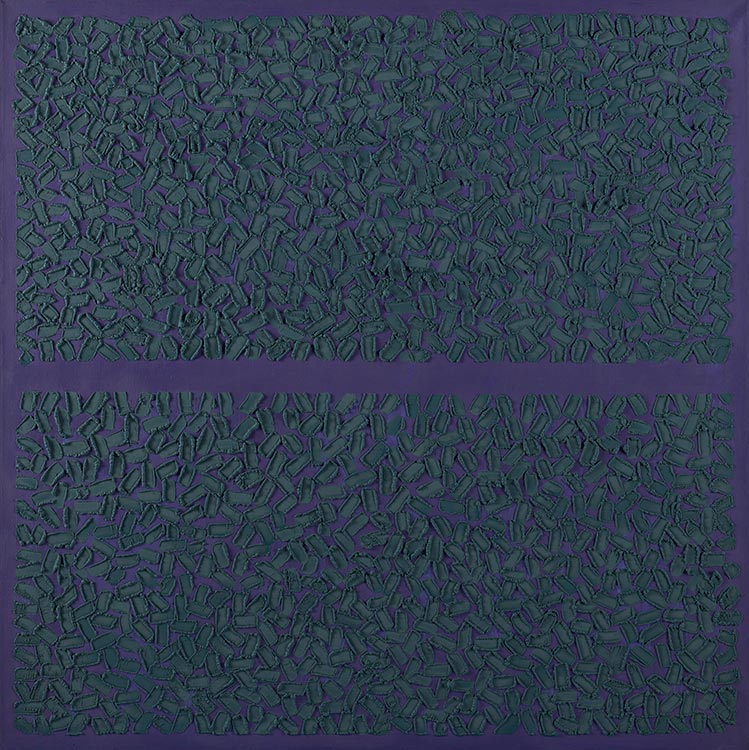

Typically, what lies beneath is unstructured, dynamic, vibrant with color, and organic, while the overlaying layer is characterized by geometric regularity, even a kind of discipline suggestive of an impersonal graph or the realm of technological and civilizational constructs—something that arbitrarily separates, like a fence, a grid, or a shutter.

Hanna Zawa completed her studies in the United States in 1980. Already in the first half of the 1980s, she created her original graphic collages and a series of objects executed in her own technique. The latter consisted of monochromatic surfaces contrasted with large, irregular forms—flat and uniformly colored, like their background—and tightly stretched, rhythmically twisted cables, usually in two different colors.

These cables formed a semi-transparent grid, at once veiling and revealing the painted composition beneath, creating a dynamic interplay between concealment and exposure.

The prints from this period, titled “Fragments of the City,” were created with the aid of a computer. In these works, the computer-generated drawing appeared as a series of delicate embossed structures, within which one could discern silhouettes of quasi-architectural forms—shapes reminiscent of buildings, repeated in varying configurations throughout the series. At the same time, these compositions contained expansive areas of intense color: vividly hued pieces of irregularly shaped paper—torn, and therefore frayed—forming indistinct outlines and pressed into the white surface of the print. Onto this prepared ground, the computer embossing was then applied.

Already in 1987, when writing about Zawa’s prints, I noted that in contrast to the automated precision of those repetitive, rhythmic embossings, the irregular forms of bright patches—orange, violet, or red—and the blurred contours created by the fibrous structure of the torn paper possessed the uniqueness characteristic of nature, utterly alien to the mechanical tool.

The artist maintains that much in her creative process happens spontaneously, almost as if by chance. Yet what role, one may ask, can chance truly play in the evolution of an artist’s work? Is it not rather the sudden discovery of something long sought after?

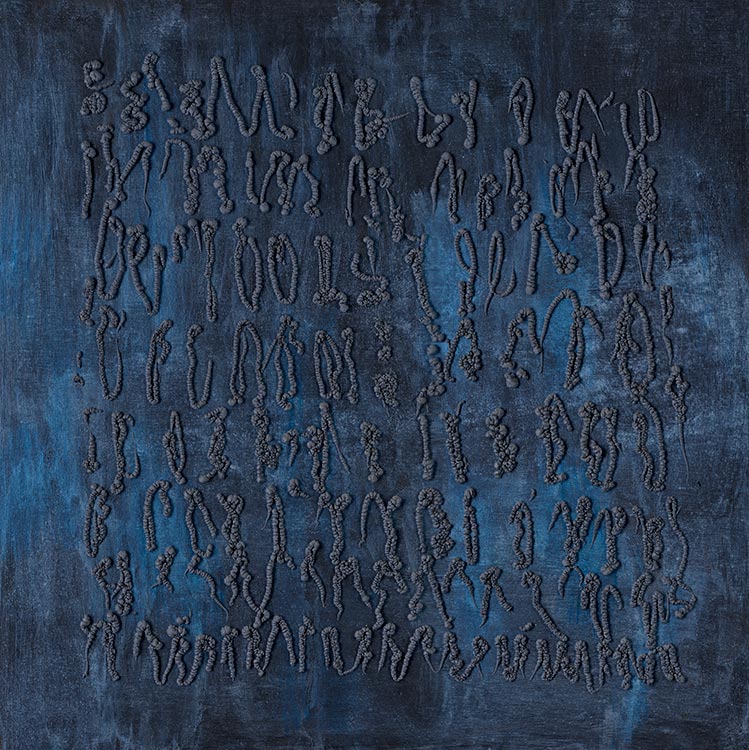

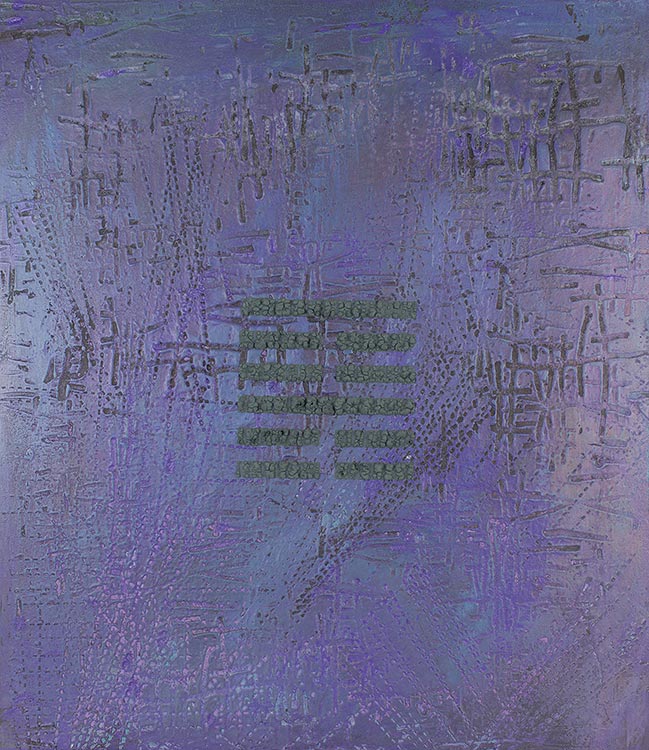

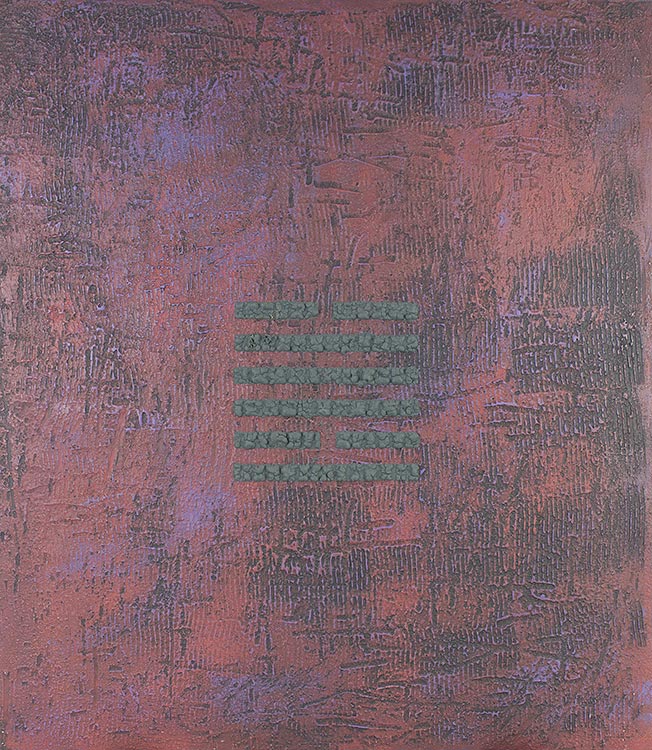

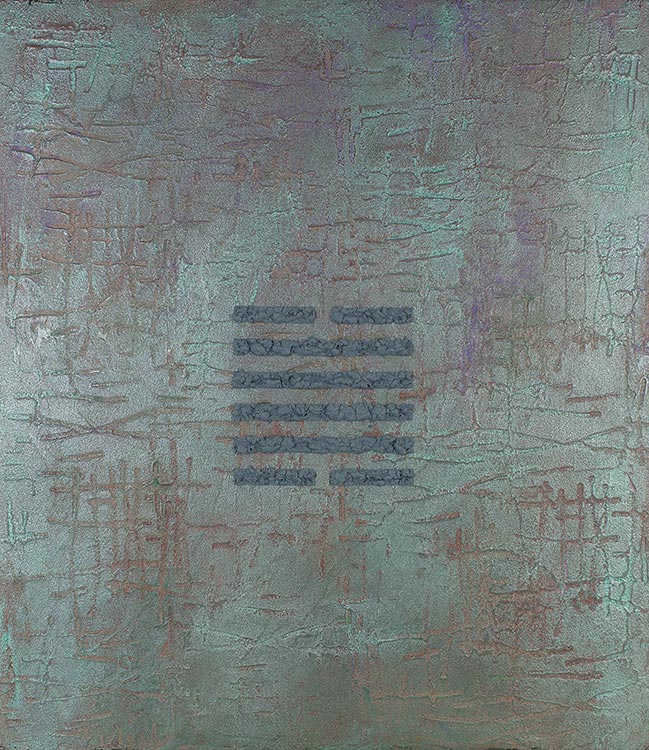

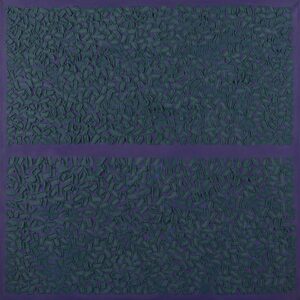

In 1987, during the Symposium for Artists Using the Language of Geometry in Okuninka, Zawa-Cywińska discovered a new material for her painting—sand from the lake shore. Mixed with paint, it began to form in her canvases a surface layer that veiled the smooth painting beneath. Through small, rectangular cutouts in this dark, monochrome upper layer, fragments of the hidden, colorful vibration underneath were revealed. It was the beginning of a long series of paintings which, as the artist explained, she hoped would be read not only as the eruption of elemental force breaking through static and ordered structure, but also as a reflection of the Far Eastern concept of illusory maya—that deceptive veil which clouds our senses and consciousness, concealing the essence of truth.

Soon after, the artist undertook experiments with a new material, used in a short series of paintings: a substance called expanser, which, under the influence of heat and depending on the duration of heating, swelled into clusters and blisters. Following her established principle, this substance formed the underlying layer of the compositions, over which she applied a geometric armor. This ordering structure, however, through the volcanic properties of the expanser, succumbed to destruction.

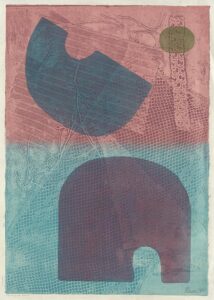

Selected Graphics from the “I-Ching” Series:

The most recent series of Zawa’s graphic works possesses a truly unique character, having been born, this time, quite literally from a chance encounter. One day, while searching for suitable papers for her planned collages, the artist visited a shop filled with old books, newspapers, and various printed materials. There she discovered a stack of trial prints—discarded lithographs by Kandinsky. It was then that the idea came to her: to combine them, following her characteristic principle, with her own linocuts.

Thus began, in 1988, a new series to which Zawa playfully gave the title “Flirt with Kandinsky.” Once again, from beneath the matte black surfaces or the rhythmic, uniform structures of linocut lines, fragments of Kandinsky’s colorful lithographic compositions emerge—through strips, geometric cutouts, and openings of various shapes—revealing glimpses of the visionary author of “The First Abstract Watercolor.”

At the same time, alongside this new graphic series, from 1990 onward Zawa-Cywińska began to paint a new body of work. The broad veils, previously opening only through sparse cutouts, gave way to dense, regular lattice structures, through which a shimmering, life-filled layer vibrates beneath the surface.

In her most recent cycles—both graphic and painterly—Zawa has achieved the mature realization of her long-evolving artistic idea. She has reached a level of true originality of expression. Yet what draws attention most in her new works is, above all, their beauty.

In the context of these new creations—and indeed of the artist’s entire oeuvre—one must ask: What is the source of this recurring interplay between unrest, movement, elemental vitality, and the counteracting presence of stillness and order? Does it reflect a direct projection of the artist’s own personality, or does she perceive this duality as a universal phenomenon—an essential principle of existence manifesting itself in all its forms?

If the latter is true, then Zawa’s art would be yet another manifestation of that principle, an echo of the same reality—only perceived on two different levels of consciousness.

Bożena Kowalska, August 1991

Selected Works from the “JAZZ” Series:

“Flirt with Kandinsky” – New Collages by Hanna Zawa

For an artist to define themselves, points of reference are essential. In times when the boundaries between what is and is not considered art are often blurred, such artistic self-definition becomes indispensable to the very existence of both the creator and their work. The present moment—freed from the notion of art’s linear evolution—draws upon tradition with increasing confidence and ease, producing, perhaps paradoxically, ever more fascinating results.

Constructivism—one of the key links in that tradition—has, for decades, inspired artists or provoked their opposition. Artists across the world have positioned themselves in relation to it. During the 1980s, as the West turned its attention to Russian art, it inevitably rediscovered Russian Constructivism, and did so on an unprecedented scale. References to the work of Malevich, El Lissitzky, and Kandinsky, as well as creative extensions of their ideas, became a common and accepted artistic strategy. The new Constructivism found many adherents within an American art scene weary of Minimalism and Conceptualism, yet reluctant to sever its ties with them completely.

Hanna Zawa is among the most intriguing New York artists engaged in this dialogue with Russian Constructivism. Actively participating in the transformations shaping American art—and responding vividly to the presence of the trend known as the strategy of image appropriation—Zawa has succeeded in consistently and consciously “appropriating” Kandinsky for herself. This was brilliantly confirmed by her most recent American exhibition, which ran until April 5 at the renowned Andre Zarre Gallery in New York. A dozen works from the same series are being presented to German audiences by Magda Potorska, beginning May 12, at her Studio-Galerie Haus am Quall in Grünten. Bringing this exhibition from New York marks yet another success for the young and ambitious gallerist.

Titled “Flirt with Kandinsky,” the show features collages in which Zawa’s predominantly black-and-white linocuts and serigraphs are overlaid with color fragments of reproductions of Kandinsky’s works. Zawa is drawn to geometry, yet—as she says—absolute purity is alien to her nature. On closer inspection, the triangles, trapezoids, and other geometric figures that form the main elements of her linocuts and serigraphs reveal themselves to be constructed from smaller, still geometric units, yet with frayed and irregular edges. Upon these, she superimposes precise, vividly colored fragments of Kandinsky’s geometric shapes. The result is as though the artist sought to oppose the Russian master’s perfection with her own “imperfection.” The confrontation, however, is harmonious, possessing a lightness and serenity that please the eye. These aesthetically refined abstract compositions evoke mysterious landscapes, part dreamlike fantasy, part science fiction.

After a period of experimenting with various materials and technologies, the artist has now focused on the emotional dimension of her work—emerging more from content than from technique. Here she has achieved complete mastery. The result is a body of original works full of warmth and joie de vivre, friendly and open, reaching out to meet the viewer. Zawa’s technical command remains, as always, virtuosic—a quality frequently noted by critics, among them John Caldwell of The New York Times. The collages possess yet another invaluable quality in today’s world: they are visually captivating.

The exhibition at Magda Potorska’s gallery marks Zawa’s second appearance in Germany. Her previous show—held at the University of Bielefeld and featuring her computer graphics—was a major artistic and commercial success. On that occasion, a reviewer wrote:

“In her computer graphics, the rational, schematic, standardized, and endlessly repeatable patterns or grids produced by the computer and imprinted on paper are transcended by the artist’s own creativity, which resists rationality through the force of the human.”